Jeff Meng, a 25-year-old watch lover from a well-heeled Guangdong family, had US$22,800 burning a hole in his pocket. He could not find the Rolex Daytona watch he wanted, dubbed “panda” for its black-and-white face, anywhere in China.

Thanks to the coronavirus pandemic that’s halted travel and disrupted networks of parallel importers, Chinese high-end shoppers like Meng – who collectively spend $111 billion a year on luxury goods, powering over a third of the global industry – are finding it hard to spend their cash.

That’s forcing global luxury houses from Balenciaga to Montblanc to rethink how to reach Chinese consumers on the mainland, despite long-standing concerns that range from counterfeiters to powerful e-commerce platforms that set the rules. The halt to travel is also fuelling the rise of a second-hand luxury market in China as consumers seek certain styles or models they can’t find in local stores.

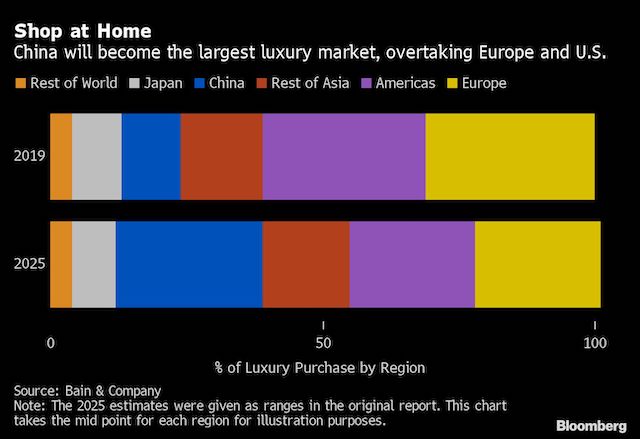

Prior to the pandemic, two-thirds of Chinese luxury purchases were made overseas, according to consultancy Bain & Co. The spending took place either on shopping spree vacations or through resellers called “daigou”. Meaning to “buy on behalf,” these were platforms or individuals who used Chinese people living, studying or travelling abroad to purchase sought-after goods from boutiques in Europe or the US and bring them back home.

“Now, travel is impossible, and daigou sellers are either back on the mainland or stranded in Europe,” said Meng. “The pandemic made me realise you can’t easily get what you fancy in China.”

From Savile Row to Swiss watches, luxury rules have changed

Cognisant of the potential of Chinese consumers who don’t travel overseas, luxury houses had already been rolling out plans to expand on the mainland. The pandemic has now hastened that shift and imbued it with urgency.

With other factors like perceived anti-Chinese racism in western countries exacerbated by the coronavirus, and the Chinese government’s desire to bring spending home to boost its ailing economy, it’s likely that Chinese luxury buyers won’t revert to previous patterns even after the crisis passes.

More than half of Chinese purchases for luxury goods will happen domestically by 2025, Bain & Co estimated in May, compared to a third in 2019.

“Chinese feel unsafe in foreign countries, which is why they consume at home,” said Amrita Banta, MD at luxury consultancy Agility Research. “Brands should increase importing from foreign countries into China and offer a wider and well-priced range. They can now expand their reach to more cities — even smaller towns which have a propensity to spend.”

E-commerce, live-streaming

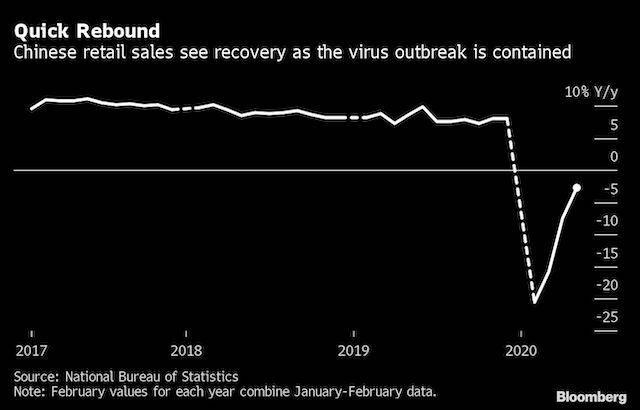

With China having largely contained its epidemic, including a new outbreak in Beijing last month, shoppers are spending again. This is set to boost the luxury market on the mainland as much as 10 per cent this year, compared to a 45-per-cent plunge in the global industry, according to estimates by Boston Consulting Group.

“Things are normal again internally, and we are seeing the results throughout our stores,” Richemont Chairman Johann Rupert said of China, where it has around 460 boutiques. “But they’re not travelling. Nobody is travelling. And until people feel sufficiently safe, I doubt that we will return to a pre-Covid stage.”

The loss of Chinese travel spending has been cited as a blow to earnings by companies from LVMH to Moncler SpA in recent months. While luxury companies mostly do not break out Mainland China numbers, sales to Chinese tourists are likely to far outstrip revenue from local boutiques, analysts say.

The trend of more spending within China “will push us to reconsider our store network,” said Jean-Marc Duplaix, CFO of Gucci-owner Kering SA during an April 21 earnings call. “It will lead to a clear re-shuffling of the distribution.”

A wave of luxury brands like Prada, Miu Miu, Balenciaga, Piaget and Montblanc have opened virtual storefronts on Alibaba Group Holding’s Tmall luxury platform this year, some setting aside long-standing objections to working with third-party online channels.

Brands like Louis Vuitton, Givenchy and Chloe have started using live-streaming to push products in China, a popular style of social commerce where an influencer speaks live to audiences for hours at a time, promoting and trying out items.

The world’s livestream queen can sell anything

In the past, luxury houses were worried about diluting brand prestige and losing control of customer data by working with Chinese internet giants like Alibaba, but the urgency of reaching Chinese shoppers has now eclipsed those concerns.

“Most luxury brands were too reliant on their offline experience and they lacked presence outside major cities where there is no decent shopping mall,” said Jason Yu, MD at Kantar Worldpanel Greater China. “Counterfeits and resellers were also prevalent on e-commerce platforms in the past. But that is fast changing now.”

Tight supply

Demand for some items has surged past supply in China. In May, Swiss watch exports to China fell 55 per cent from a year ago, according to industry data, largely due to supply bottlenecks.

“Due to the travel curbs during the pandemic, all the consumption power is locked inside China, so our sales there are growing,” said Alain Lam, the finance director of Oriental Watch Holdings. The high-end watch seller has 46 stores in mainland China. “But the supply is very tight, as Swiss factories are not yet fully returned to work.”

Prior to the pandemic, luxury brands largely avoided stockpiling in China and kept local manufacturing to a minimum. Brands will now need to rethink how to avoid delayed stock and lost sales, said Agility’s Banta.

Chinese shoppers desperate for certain items are turning to second-hand luxury platforms to procure them, fueling a surge of investment in such startups. Jeff Meng finally found his “panda” Rolex watch on one such platform called Ponhu (Beijing) Technology.

Boosted by the pandemic, Ponhu’s gross sales will triple this year compared to last year, said founder Ma Cheng.

JD’s used-goods platform Paipai saw sales in second-hand luxury goods jump 138 per cent during the 18 days of its annual summer sale period in June compared to a year ago, including a record 300 Rolex timepieces changing hands. The demand for luxury watches in particular is due to the delay of new stock supply to Chinese retail stores, said Paipai’s luxury business manager Tony Yao.

Rise of Hainan

Facing its worst economic contraction since at least 1992, when official data was first released, China wants to keep spending within its borders.

On July 1, China increased the tax-free shopping quota for travellers to its southern Hainan province, which has been designated a free trade zone, to 100,000 yuan annually per person from the previous 30,000 yuan. Sales on the first day of the new policy at four malls amounted to nearly 60 million yuan, reported state media.

Some Chinese consumers say that the pandemic has unexpectedly shifted their perspectives: shopping at home can be convenient and pleasant in contrast to infrequent vacations or daigou platforms with no-returns policies.

“I realise it’s so nice that I can try on the clothes in the malls, and salespeople treat me as a long-term client instead of just a tourist,” said Michelle Zhang, a finance executive from Fuzhou, Fujian province. “Even after global travel resumes, I will continue to shop more at home.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.